The DU Lounge

Related: Culture Forums, Support ForumsDeparture.

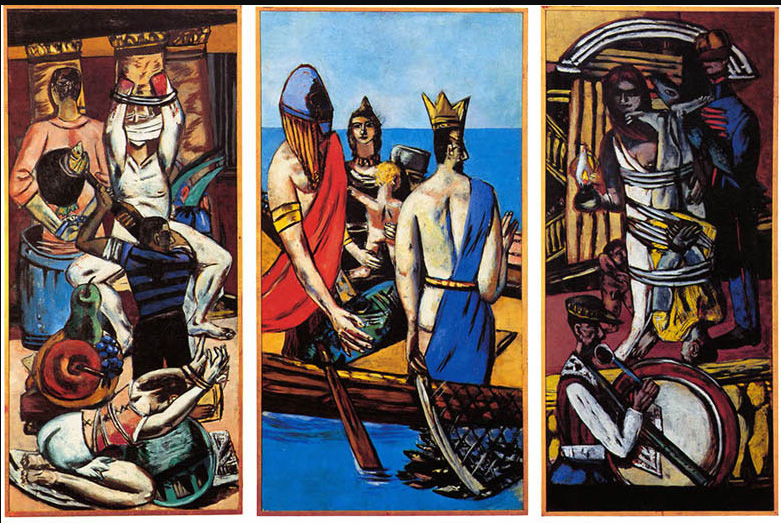

Max Beckmann, 1884-1950 ( German, American after 1947)

Painted 1932-1935.

At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

If you find yourself in New York, I strongly suggest you spend some time before this painting. For me, it is very much like the experience of standing in front of Picasso's Guernica, as I did as young man, when it was temporarily at the Metropolitan Museum awaiting the end of fascism in Spain.

The painting is Beckmann's comment on fascism; he left Germany only to become trapped in Europe during the German occupation of the Netherlands. After the war, he emigrated to the United States, then and hopefully again, a beacon of freedom.

The Modern's short biographical sketch:

After he received initial recognition for history paintings and portraits, with muted palettes, an impressionistic paint handling, and references to Old Masters like Michelangelo and Peter Paul Rubens, the course of Beckmann’s life and art shifted at the outbreak of World War I. He joined the medical corps, and at first he was energized by the turmoil of war, writing “my art can gorge itself here.”1 But the action soon ended for him after he had a nervous breakdown in 1915. Over the next decade, he captured the doomed Weimar Republic with acidic cynicism, creating jam-packed, riotously colored canvases populated by a cast of characters enacting the chaos of postwar urban life. He also focused on etching and lithography in these years, producing several black-and-white print portfolios, including Hell (1918–19), which features scenes of a devastated Berlin. The city’s inhabitants torture one another, clamp their eyelids shut, and dance frantically.

In the early 1930s, the National Socialist press began to attack Beckmann’s work, and in 1933, soon after Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany, the artist was dismissed from his teaching position at Frankfurt’s Städel Art School, and his paintings at the Berlin National Gallery were removed from view. It was in this time of mounting terror and uncertainty that Beckmann began to paint the triptych Departure (1932–35), in which he has juxtaposed restraint and freedom, compression and openness, violence and refuge. Its outer panels are consumed by scenes of torture in a dimly lit theater, while in the center panel archaic figures appear on a boat in calm seas under a clear, bright sky.

In 1937, on the day after many of his works were included in the Degenerate Art exhibition, Beckmann left for Amsterdam, where he lived during World War II. He remained active in exile, turning to mythic, parabolic images unmoored from a particular time or place. In 1947, he was able to immigrate to America, where he taught in St. Louis and New York. Sharing his own mantra with his students, he often told them, “work a lot…simplify…use lots of color…make the painting more personal.”

Max Beckmann died in New York, on Central Park West and 69th street, on his way to see one of his paintings exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum, which held a retrospective a few years back, which I attended with my wife and sons. (This painting was on loan for that exhibit.)

As is the case with Guernica, one cannot understand or feel the painting if one sees a reproduction in a book or on the internet. It is a large triptych, though it could never be as big as the crime it evokes. I cannot stand before it without tears in my eyes.

If i were to point out one of the most creepiest aspects of art it would be Guernica. That fucking light bulb. I don't think i could handle it without crying...

NNadir

(34,710 posts)...been attacked by vandals, another crime, like what it depicts, against humanity.

It's not the same, up high, out of reach, as it was when it was displayed at the Met. I went to see it, just before it left New York in 1981, to say good-bye, but saw it many times before that. You could stand right in front of it, struck by the enormity.

It goes without saying that it was a moving experience.

Seeing Departure is a similar experience for me. I went to the Modern with my son when he was an art student. I will never forget going up the escalator and as you stepped off, there it was, Departure. I will always remember that day with my son, that moment in particular.