Latin America

Related: About this forumYou may want to know why killer gangs destroy pine forests and assassinate activist defenders

of the forests and terrorize those they haven't murdered yet. You also need to know they are doing this in the one area in Mexico where the entire disappearing Monarch Butterfly has always wintered forever, apparently.

Here's a simple explanation:

Date: July 21, 2020

Author: Lifestyle Collective

By Pieter De Wit

Remarkably, I can still remember the exact moment my sister introduced me to my very first avocado. I spooned out one half and savoured the full taste and unusual texture. Since then, I have had my share of avocados in salads, on bread, in smoothies, and of course in the best dip of all: guacamole.

My friends know me as the healthy one, some of them use the word freak, so upon discovering the health benefits of this green fruit, they became a staple of my diet. Mostly known for its healthy monounsaturated fats, associated with reduced inflammation and having a beneficial effect on genes linked to cancer, avocados also have a wide variety of nutrients with 20 different vitamins and minerals. They even beat bananas in the richness of potassium, a mineral known to reduce blood pressure.

But this “green gold”, native to central Mexico and the Michoacán state particularly, is unfortunately not so healthy for the wellbeing of the local workers and the environment. In South America, the avocado industry is ruled by the mafia groups afflicting the region. The fruit needs tons of water during the growing process, leading to serious droughts. Such is its value, many forests have been cleared illegally to pave the way for avocado farms. People are now rethinking their consumption, and some restaurants have even stopped serving this forbidden fruit.

The New Mafia

The export of Michoacán avocados reached a turnover of over $2.8 billion USD in 2019. And the criminal groups want their share. One of the main cartels ruling the farms are the Viagras. In March 2019 they imposed a tax on residents who own avocado trees, charging $250 USD a hectare in exchange for so-called protection. But of course, the Viagras are not alone and are fighting bloody wars for local power.

One of their rivals is the Caballeros Templarios cartel, who are not shy to torture or kill anyone who refuses to pay their taxes. The term ‘blood avocados’ refers to the violation of human rights by these cartels who rule in the region.

For decades the cartels have used avocado farms to launder money, and now they clear protected woodlands to plant their own groves of the green gold.

Additionally, state officials record an average of four avocado transport trucks being hijacked each day, but President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador is failing to protect transporters, farm owners and fruit pickers. In response to the lack of action by the authorities, avocado producers took drastic measures and set up their own civilian police force, which has had a modicum of success in creating a safer environment.

Environmental Effects Of Avocado Farming

Water Shortage

1. One report estimates that on average, you need approximately 283 litres of water to produce about half a kilogram of avocados. In regions like Chile, it takes up to 320 litres of water to grow one single avocado. In contrast, for tomatoes, this can be as little as 5 litres. In the search for more water, private plantations installed illegal pipes and wells to divert water from rivers to irrigate their crops.

More:

https://lifestylecollective.org/2020/07/21/its-time-you-knew-the-ugly-truth-behind-the-avocado/

~ ~ ~

You may want to know why killer gangs destroy pine forests and assassinate activist defenders

Did Avocado Cartels Kill the Butterfly King?

Homero Gómez González put himself between a threatened species and Mexico’s avocado and timber industries. Then he disappeared.

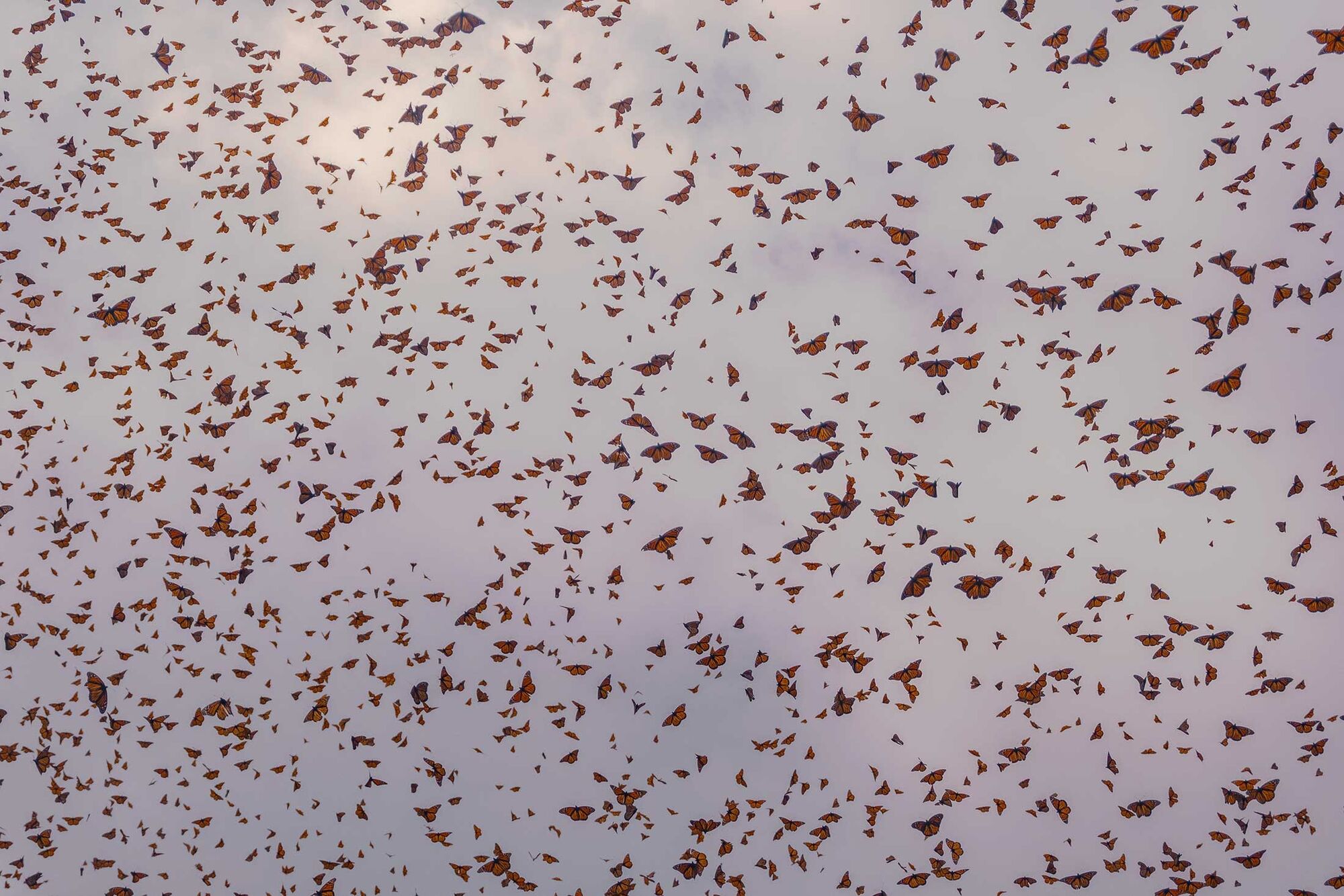

Butterflies wintering at the El Rosario sanctuary in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve.Photographer: Fred Ramos for Bloomberg Businessweek

By Matthew Bremner

July 23, 2021 at 4:00 AM CDT

At midday on Jan. 13, 2020, Homero Gómez González, one of Mexico’s most respected conservationists, attended his final meeting. Like most of his appointments, this one was about butterflies. For years, Gómez had been the leading defender of the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, a collection of sanctuaries in Michoacán, about a two-hour drive west of Mexico City, that attracts swarms of orange-and-black butterflies migrating south for the winter, some of them the size of a small dinner plate. The migratory phenomenon, recognized by the United Nations as a cultural heritage worthy of protection, draws millions of monarchs from as far as Canada and Alaska and, in pre-pandemic times, some 300,000 tourists.

That day in January, the middle of butterfly season, Gómez was visiting the monarch sanctuary in a village called El Rosario. In most ways, attendees recall the meeting as unremarkable, focused on the sanctuary’s finances, visitors, and tree plantings. If there was one odd thing, they say, it was that Gómez’s phone was buzzing the entire time. They’d seen the butterfly activist, a onetime community president, get lots of calls from tourist agencies, politicians, and journalists. But this barrage seemed relentless. Eventually, Gómez picked up.

Whoever was on the other end of the line seemed to want Gómez to attend the final day of a local fair in the town of El Soldado, according to people who overheard the call, including Miguel Angel Cruz, the current community president. The caller told Gómez the fair was an important local event, noting the horse racing, gambling, alcohol, and many local politicians sure to attend. “Yes, yes, of course I’m going,” Cruz and others heard him reply.

After the meetings finished, Gómez drove the 40 minutes to the fairgrounds, arriving at around 5 p.m., according to his family. He parked his red Seat Ibiza next to a bunch of similar cars in a field near the racetrack. The day was overcast but mild. The grounds sprawled with flapping white tents and hordes of people held back from the sandy track by white metal barriers. Jockeys paraded the paddocks while their horses nickered and snorted. Among the bobbing Stetson hats, jeans, chunky belt buckles, and botas picudas (pointy boots), Gómez wore a white guayabera shirt, grayish suit trousers, and brown shoes. He was 50 years old, chunky, and square-headed, with a thick shoe-brush mustache bristling beneath his ski-jump nose.

Gómez was famous in these circles. Locals beckoned and greeted him wherever he went, attendees say. They included the politician Elizabeth Guzmán Vilchis, who was hosting a lunch for influential local officials. As afternoon crept into evening, the music and the crowd swelled, but Gómez kept schmoozing amicably. “We danced, drank, joked, and laughed,” Guzmán says. “There was no tension between anybody.” She last saw him at 8 p.m., when she took her kids home. Others say they spotted him in one of the tents about an hour later. After that, he was never seen alive again.

The news of Gómez’s disappearance spread quickly. There were articles in the national press, followed by accounts from the BBC, NPR, and the Washington Post. Experts speculated that whatever had happened to him was tied to his activism.

Rebeca Valencia, Gómez’s wife, had always been ill at ease about her husband’s work. Now she felt paralyzed with fear. In the village of Rincón de San Luis, several miles away from the sanctuary, she stared at her phone. There were no messages, no signs of life.

Valencia, her round face puffy and her eyes brimming with tears, had good reason to worry. The state of Michoacán was rich with international trafficking routes, exploitable pine and fir forests, and the billion-dollar avocado trade. And for the past several years, the state had been caught in a brutal war. On one side was the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, Mexico’s fastest-growing criminal organization. On the other, a collection of local groups defending their home territory under the banner of United Cartels. The conflict had become so violent that many politicians and police had stopped fighting and joined forces with the cartels. It was often difficult to separate the mafia from the state.

For people who tried to disrupt this collusion, there were always consequences. “There was plenty of friction between him and powerful people,” says Amado, Gómez’s brother.

. . .

“My dad always lived without fear,” says Homero Jr. Photographer: Fred Ramos for Bloomberg Businessweek

. . .

Every fall since the mid-1970s, Homero Gómez Gonzalez, the eldest of nine siblings, had watched millions of monarchs migrate to the butterfly sanctuaries near his home. He saw how the insects blanketed thousands of firs like leaves. His grandparents had told him the monarchs were the spirits of their ancestors, returning every year to rest on the Day of the Dead. Gómez respected these myths.

. . .

Throughout Mexico, two dozen environmental activists were killed the year before Gómez disappeared, according to Amnesty International. And Michoacán, his home state, is one of the most violent overall, with 1,309 murders in the first 10 months of 2020. The state contains essential drug-smuggling routes, and in recent years it wasn’t unusual to see rival cartels shooting at each other during the day in the larger cities and towns.

One of the reasons for the gun violence is avocados. From 2001 through 2018, the annual consumption of avocados in the U.S. increased by 5.5 pounds a person, to 7.5 pounds a person. Of those avocados, 87% came from Mexico, and most from Michoacán, whose high rainfall and rich soil have made it the avocado capital of the world. The industry is worth $2.4 billion annually, it pays workers as much as 12 times Mexico’s minimum wage, and it offers high profit margins for local landowners. The money attracts criminals looking for safer alternatives to the drug trade.

The competition for the business in Mexico is fiercer than anywhere else. Four cartels are said to be fighting over avocados in Michoacán, including perhaps the country’s most violent, Jalisco New Generation Cartel. The violence has at times seemed medieval. In August 2019, 19 people were murdered in Uruapan, their body parts exhibited at three different sites around the city.

Much of the avocado trade, and the violence, has been in the central part of the state, a few hundred miles away from the wintering butterflies. Still, tourism fell as many would-be visitors decided not to risk running afoul of the cartels. This, in turn, made a slew of new avocado mini-plantations all the more important to the region.

. . .

Today, Gómez’s case is stalling. Valencia, who knows full well where she lives, is skeptical. Michoacán is a place where organized crime and the state exist in some symbiosis. Out of Mexico’s 32 federal entities (31 states plus Mexico City), Michoacán is ranked as the most corrupt as perceived by its own residents, according to a 2019 poll by Mitofsky, a consulting company in Mexico City. Police in Michoacán solve only 3% of the state’s homicide cases. “On the one hand, there may be powerful people stopping the investigation, and on the other, there is a problem of resources and an inability to investigate the case properly,” says Bernardo León Olea, a former Morelia police commissioner.

More:

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2021-07-23/did-the-avocado-cartel-kill-mexico-butterfly-king-homero-gomez-gonzalez

Homero Gómez González

Rebeca Valencia Gonzalez