Latin America

Related: About this forumStudents from the entire world, inchuding the US, have been educated in Cuba

The agreement calls for them to work for a period of time when they get home among the poor with people who couldn't have otherwise afford medical treatment.

Have been posting this information here, along with some DU'ers who have personal knowledge of this arrangement, since at least as far back as 2002.

The charge of "slavery" has been thrown against the Cuban government by the radical right-wing racist Cuban "exiles" who populated South Florida and New Jersey for many years, in an attempt to create hatred of the revolution, and Cuban doctors who have been doing medicine for the right reason from the first. Cuban doctors have been loved and celebrated all over the world, often being the first to areas hit by hurricanes, earthquakes, disease, serving in the areas conventional money-motivated doctors would refuse to visit, among the poor.

Here's one reference. You can find more information by simply looking for it on the "system of tubes", the "Internets", as the late Senator/idiot from Alaska once defined it, Senator Ted Stevens, proud Republican and major grifter.

~ ~ ~

Who are the Americans who are going to study medicine in Cuba?

Thursday, June 28, 2018

American Sarpoma Sefa-Boakye discovered that she wanted to be a doctor at the age of nine. Born in southern California, the daughter of Ghanaian immigrants, she says that on her first trip to Africa for a funeral in her parents' homeland she was moved by poverty.

"I thought one way to help would be to become a doctor," Sarpoma, 39, tells BBC News Brazil.

When it came time to enter the medical school - which is offered in the United States as a graduate student - Sarpoma enrolled in American universities, but instead chose a less usual destination: the Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM) in the capital Cuban, Havana.

According to her, what weighed in the decision was the possibility to finish the course without debts, since the Cuban government offers scholarships to the American students.

"I thought, 'Am I going to be able to afford a course in medicine in the United States, which costs between $ 200,000 and $ 300,000?'" He recalls.

Sarpoma is part of a group of 170 American doctors trained by ELAM, most of them black or Latino.

It may sound strange that citizens of a rich country like the United States participate in a program aimed at young people from low-income communities. But in American, Black and Latino colleges account for less than 6% of medical graduates.

"Most black and Latino students can not afford to pay for the medical course in the United States," says Melissa Barber, a graduate of ELAM in 2007 and the coordinator of the program that selects American students for Cuban school to IFCO (Interreligious Foundation for Community Organization, in Portuguese), in New York.

In contrast, 47% of Americans trained by ELAM are black and 29% are Latino. In exchange for the free course, they undertake to work in areas lacking medical services when they return to their country.

Founded in 1999 to provide free education to young people from poor nations in Central America and the Caribbean affected by hurricanes Mitch and Georges, ELAM today brings together students from 124 countries.

The first Americans arrived in 2001 after leaders of Congressional Black Caucus, the group of black congressmen from the United States, visited the island and reported the shortage of doctors in some minority areas in their country. The Cuban leader at the time, Fidel Castro, offered scholarships to low-income Americans.

The selection of candidates is the responsibility of the IFCO, an institution that opposes the economic embargo imposed by the United States on Cuba. The final decision lies with ELAM.

"Every year, we receive 150 applications on average, of which about 30 actually enroll, and 10 are sent to Cuba," says Barber.

The course lasts six years, two more than in the United States. There is also an additional year, at the beginning of the course, dedicated to preparatory classes focusing on science and Spanish.

Despite the tension in relations between the two countries, the ELAM-trained Americans guarantee that the program leaves politics out. "Some people think that students are going to be used as a political tool on both sides, but that's not true, we're only there to study medicine," says Sarpoma.

Injections on the first day

The scholarship includes dormitory accommodation, three meals a day in the campus cafeteria, books in Spanish, a uniform and a small monthly financial aid.

Students are warned about "Spartan" accommodations, unlike what they are accustomed to in their country, and difficulties such as an occasional lack of energy and little access to the internet. But what most surprised Sarpoma was the method of education, focused on prevention and interactions with patients from the outset.

"In the United States, schools use actors to play the role of patients, not in Cuba, you learn in the clinic."

Barber highlights the community aspect of the Cuban system. "Teams formed by a doctor and a nurse are responsible for a small geographic area, they know that community. Patients go to the clinic, and the professionals also go from house to house."

In making the diagnosis, doctors are encouraged to consider biological, psychological, and social elements. "You are looking at the full picture, what is happening in the life of this patient, including social and environmental factors, that can cause these symptoms," he says.

More:

https://members.nmanet.org/news/407131/Who-are-the-Americans-who-are-going-to-study-medicine-in-Cuba.htm

Judi Lynn

(163,195 posts)👂Hear from US Medical Students at the Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM), Nzingha Bomani and Sarah Almusbahi sharing their experiences studying medicine in Cuba!

🩺Want a FULL scholarship to study medicine? Do you know anyone who does? Here's how

~ ~ ~

Cuba’s Medicine Program: High-Quality Education for American Students

July 2, 2024by CubaHeal Research

Choosing the right destination for medical studies is a pivotal decision for any aspiring doctor. While many students might consider the United States, Canada, or Europe, an increasingly popular yet often overlooked destination is Cuba. Renowned for its high-quality medical education, rich culture, and the added advantage of gaining proficiency in a second language, Cuba offers a unique and compelling proposition for North American students.

Exceptional Medical Academic Programs

Cuba’s medical education system is internationally acclaimed, offering robust and comprehensive programs that are both rigorous and affordable. The University of Medical Sciences of Havana is one of the most prestigious medical schools in the country, known for its high standards and quality education. This institution provides a strong foundation in medical sciences and extensive clinical training, making it an excellent choice for North American students.

More:

https://cubaheal.com/2024/07/02/why-north-american-students-should-study-medicine-in-cuba-affordable-high-quality-education-and-cultural-immersion/

Meet the U.S. Students Studying Medicine For Free in Cuba

https://www.instagram.com/ifco_p4p/reel/DF8u9Z0RYhW/

YouTube:

~ ~ ~

After 63 years of the US blockade, Cuba still educates international doctors for free

February 5, 2025

The closing ceremony of the 25th Anniversary Congress of ELAM Graduates, held at the Convention Center in Havana, was presided over by the Cuban Minister of Health, Cuban Minister of Foreign Affairs and the Rector of the ELAM.

by JR Valrey, The Minister of Information

Dr. Samira Addrey is a class of 2020 alumni of the Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM) and an organizer with IFCO/Pastors For Peace who is currently giving out scholarships for ELAM. The ELAM scholarships were created by the Cuban government to help develop health and wellness services for underserved communities around the world.

Recently, the US and Israel – against the rest of the international community – succeeded in keeping a 63-year blockade of the nation in place at the United Nations.

Within the last two months, Cuba has been hit with nationwide blackouts caused by shortages that the blockade created, a renewal of the blockade, two hurricanes and two earthquakes.

Dr. Addrey recently visited the island and was gracious enough to give us a reportback from the ground about the recent damage that has occurred because of the disasters, the damage caused by the decades-long illegal blockade being renewed, as well as to let us know that the Cubans will continue to fight the Revolution against capitalism and imperialism worldwide.

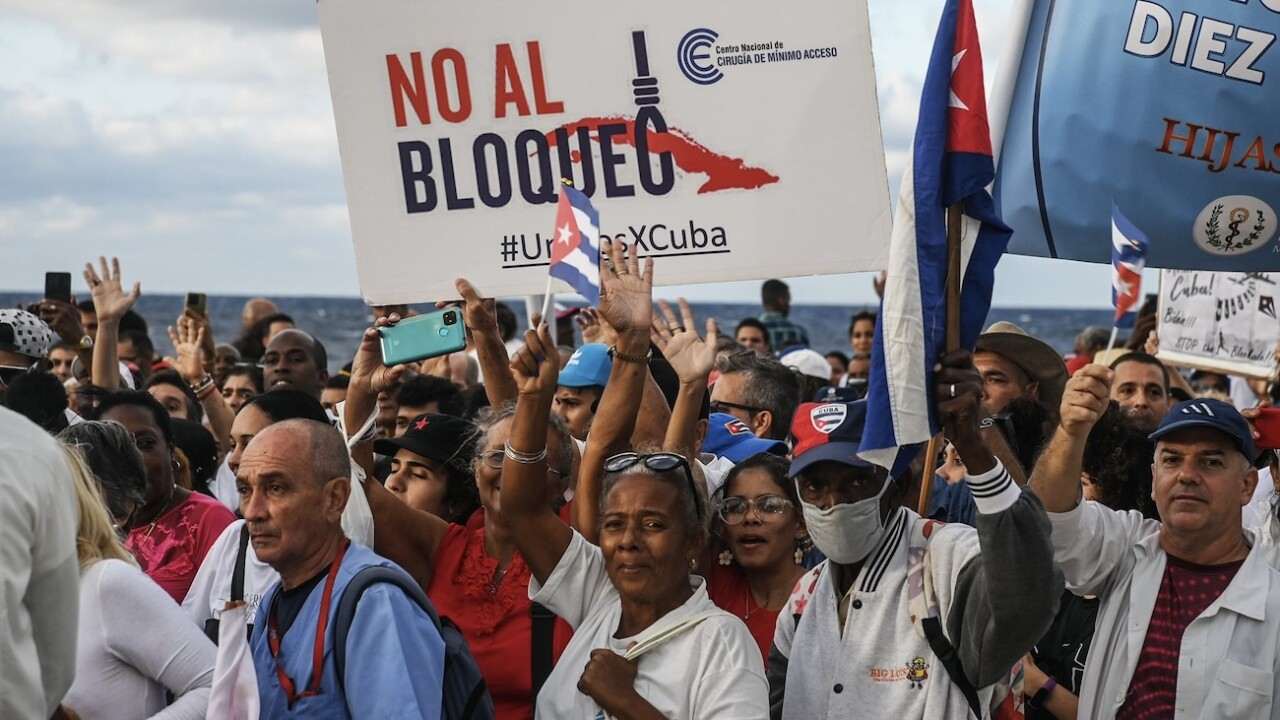

over-half-a-million-cubans-filled-the-malecon-in-a-massive-march-against-the-us-blockade-122024-by-presidencia-cuba, After 63 years of the US blockade, Cuba still educates international doctors for free, Featured World News & Views

Over half a million Cubans filled the Malecón on Dec. 20 in a massive march against the six-decade US blockade of Cuba and the inclusion of Cuba on the US state sponsors of terrorism list. – Photo: Presidencia Cuba

More:

https://sfbayview.com/2025/02/after-63-years-of-the-us-blockade-cuba-still-educates-international-doctors-for-free/

Judi Lynn

(163,195 posts)By

Helen Yaffe

The United States calls Cuba’s medical internationalism "human trafficking" — but it’s really an internationalist lifeline for the Global South.

On February 25, US secretary of state Marco Rubio announced restrictions on visas for both government officials in Cuba and any others worldwide who are “complicit” with the island nation’s overseas medical-assistance programs. A US State Department statement clarified that the sanction extends to “current and former” officials and the “immediate family of such persons.” This action, the seventh measure targeting Cuba in one month, has international consequences; for decades tens of thousands of Cuban medical professionals have been posted in around sixty countries, far more than the World Health Organization’s (WHO) workforce, mostly working in under- or unserved populations in the Global South. By threatening to withhold visas from foreign officials, the US government means to sabotage these Cuban medical missions overseas. If it works, millions will suffer.

Rubio built his career around taking a hard line on Cuban socialism, even alleging that his parents fled Fidel Castro’s Cuba until the Washington Post revealed that they migrated to Miami in 1956 during the Fulgencio Batista dictatorship. As Trump’s secretary of state, Rubio is in prime position to ramp up the belligerent US-Cuba policy first laid out in April 1960 by deputy assistant secretary of state Lester Mallory: to use economic warfare against revolutionary Cuba to bring about “hunger, desperation and overthrow of government.”

Cuba stands accused by the US government of human trafficking, even equating overseas Cuban medical personnel to slaves. Rubio’s tweet parroted this pretext. The real objective is to undermine both Cuba’s international prestige and the revenue it receives from exporting medical services. Since 2004, earnings from Cuban medical and professional services exports have been the island’s greatest source of income. Cuba’s ability to conduct “normal” international trade is currently obstructed by the long US blockade, but the socialist state has succeeded in converting its investments in education and health care into national earnings, while also maintaining free medical assistance to the Global South based on its internationalist principles.

The four approaches of Cuban medical internationalism were initiated early in the 1960s, all despite the post-1959 departure of half of the physicians in Cuba.

1. Emergency response medical brigades. In May 1960, Chile was struck by the most powerful earthquake on record, with thousands killed. The new Cuban government sent an emergency medical brigade with six rural field hospitals. This established a modus operandi under which Cuban medics mobilize rapid responses to “disaster and disease” emergencies throughout the Global South — since 2005 these brigades have been organized under the name “Henry Reeve International Contingents.” By 2017, when the WHO praised the Henry Reeve brigades with a public health prize, they had helped 3.5 million people in twenty-one countries. The best-known examples include brigades in West Africa to combat Ebola in 2014 and in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Within one year, Henry Reeve brigades treated 1.26 million coronavirus patients in forty countries, including in Western Europe.

2. Establishment of public health care apparatuses abroad. Starting in 1963, Cuban medics helped establish a public health care system in newly independent Algeria. By the 1970s, they had set up and staffed Comprehensive Health Programs all throughout Africa. By 2014, 76,000 Cuban medical personnel had worked in thirty-nine African countries. In 1998, a Cuban cooperation agreement with Haiti committed to send 300 to 500 Cuban medical professionals there all while training Haitian doctors back in Cuba. By December 2021, more than 6,000 Cubans medical professionals had saved 429,000 lives in the poorest country in the western hemisphere, conducting 36 million consultations. And for two decades now, Cuba has maintained over 20,000 medics in Venezuela, peaking at 29,000. In 2013, the Pan American Health Organization contracted 11,400 Cuban doctors to work in under- and unserved regions of Brazil. By 2015, Cuban Integral Healthcare Programs were operating in forty-three countries.

3. Treating foreign patients in Cuba. In 1961, children and wounded fighters from Algeria’s war for independence from France went to Cuba for treatment. Thousands followed from around the world. Two programs were developed to treat foreign patients en masse: The first is the “Children of Chernobyl” program which began in 1990 and lasted for twenty-one years, during which 26,000 people affected by the Chernobyl nuclear disaster received free medical treatment and rehabilitation on the island — nearly 22,000 of them children. The Cubans covered the cost, despite the program coinciding with Cuba’s severe economic crisis, known as the Special Period, following the collapse of the socialist bloc. The second program to treat foreign patients en masse was Operation Miracle, set up in 2004 for Venezuelans with reversible blindness to get free eye operations in Cuba to restore their sight. It subsequently expanded regionally. By 2017, Cuba was running sixty-nine ophthalmology clinics in fifteen countries under Operation Miracle, and by early 2019 over four million people in thirty-four countries had benefited.

4. Medical training for foreigners, both in Cuba and overseas. It’s important to note that the Cuban state never sought to foster dependence. In the 1960s, it began training foreigners in their own countries when suitable facilities were available, or in Cuba when they were not. By 2016, 73,848 foreign students from eighty-five countries had graduated in Cuba while that nation was running twelve medical schools overseas, mostly in Africa, where over 54,000 students were enrolled. In 1999, the Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM), the world’s largest medical school, was established in Havana. By 2019, ELAM had graduated 29,000 doctors from 105 countries (including the United States) representing 100 ethnic groups. Half were women, and 75 percent from worker or campesino families.

More:

https://jacobin.com/2025/03/cuba-medical-programs-us-sanctions

Judi Lynn

(163,195 posts)12 September 2014

Note for Media Reading time: Less than a minute (255 words)

WHO welcomes the commitment from the Government of Cuba to provide 165 health professionals to support Ebola care in west Africa. The newly announced support includes physicians, nurses, epidemiologists, specialists in infection control, intensive care specialists and social mobilization officers, and will be concentrated in Sierra Leone.

"If we are going to go to war with Ebola, we need the resources to fight," says Dr Margaret Chan, Director-General of the World Health Organization. “I am extremely grateful for the generosity of the Cuban government and these health professionals for doing their part to help us contain the worst Ebola outbreak ever known. This will make a significant difference in Sierra Leone.”

The WHO Ebola response roadmap, released on 28 August, highlights the need for a massively scaled response to support affected countries. The commitment from the Cuban government exemplifies the kind of international effort required to intensify response activities and strengthen national capacities.

“Cuba is world-famous for its ability to train outstanding doctors and nurses and for its generosity in helping fellow countries on the route to progress,” says Dr Chan.

The health professionals will deploy to Sierra Leone the first week in October and stay for 6 months. They have all worked previously in Africa.

https://www.who.int/news/item/12-09-2014-who-welcomes-cuban-doctors-for-ebola-response-in-west-africa

Judi Lynn

(163,195 posts)14 April 2015

Dr Felix Sarria Baez was one of hundreds of Cuban doctors sent as a Foreign Medical Team to support the Ebola response in West Africa in October 2014. While working there, he contracted Ebola himself. He survived and returned to Sierra Leone to further help Ebola patients. Below is his story.

Dr Felix Sarria Baez, Cuban doctor, returns to Sierra Leone after recovering from Ebola.

"It’s been like coming back from a war, alive. My companeros shouted, smiled, cried and hugged me," Dr Felix Sarria Baez reflected on his return to Sierra Leone after recovering from Ebola.

Dr Felix told his story on a hot, dusty hotel patio in Port Loko, a 2-hour drive from the capital Freetown. He was wearing a new WHO polo, a gift when he came back to Sierra Leone. All his other clothes were destroyed in November 2014 when he was diagnosed with Ebola. "It’s good to come back. I needed to come back," he explains. "Ebola is a challenge that I must fight to the finish here, to keep it from spreading to the rest of the world."

Becoming infected

"I don't know how I got infected. There was no violation of protocols," he explains, describing sweat "like a river" from the layers of heat-retaining safety garments that cause body surface temperatures to rise to 40 degrees centigrade (104 Fahrenheit). This is significantly higher than normal body temperature of 37° C (98.6 F) and can only be withstood for 40 to 60 minutes. WHO provided rigorous safety training and mentoring to the Cuban Medical Brigade and other foreign medical teams before starting work in the Ebola treatment centers.

Dr Felix remembers clearly the day he first felt ill. "It started Sunday morning with a fever of 38 and then 39.5° C (100.4 to 103.1 F). I lost my appetite all day, but I didn’t feel weak or have any pain," he recounted.

"On Monday, I went to Kerry Town Treatment Unit, where there is a special ward for health care workers. I developed a cough that lasted throughout my illness. My white blood cell count and platelets fell fast. At 8 p.m. the test result came back positive for Ebola." White blood cells fight infection and platelets help blood clot. Without them, the body risks succumbing more quickly to Ebola.

More:

https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/cuban.-doctor.-ebola-survivor

Judi Lynn

(163,195 posts)This article is more than 10 years old

The island nation has sent hundreds of health workers to help control the deadly infection while richer countries worry about their security – instead of heeding UN warnings that vastly increased resources are urgently needed

Monica Mark in Lagos

Sat 11 Oct 2014 19.05 EDT

As the official number of Ebola deaths in west Africa’s crisis topped 4,000 last week – experts say the actual figure is at least twice as high – the UN issued a stark call to arms. Even to simply slow down the rate of infection, the international humanitarian effort would have to increase massively, warned secretary-general Ban Ki-moon.

“We need a 20-fold resource mobilisation,” he said. “We need at least a 20-fold surge in assistance – mobile laboratories, vehicles, helicopters, protective equipment, trained medical personnel, and medevac capacities.”

But big hitters such as China or Brazil, or former colonial powers such France and the UK, have not been stepping up to the plate. Instead, the single biggest medical force on the Ebola frontline has been a small island: Cuba.

That a nation of 11 million people, with a GDP of $6,051 per capita, is leading the effort says much of the international response. A brigade of 165 Cuban health workers arrived in Sierra Leone last week, the first batch of a total of 461. In sharp contrast, western governments have appeared more focused on stopping the epidemic at their borders than actually stemming it in west Africa. The international effort now struggling to keep ahead of the burgeoning cases might have nipped the outbreak in the bud had it come earlier.

André Carrilho, an illustrator whose work has appeared in the New York Times and Vanity Fair, noted the moment when the background hum of Ebola coverage suddenly turned into a shrill panic. Only in August, after two US missionaries caught the disease while working in Liberia and were flown to Atlanta, did the mushrooming crisis come into clear focus for many in the west.

“Suddenly we could put a face and a name to these patients, something that I had not felt before. To top it all, an experimental drug was found and administered in record time,” explained the Lisbon-based artist. “I started thinking on how I could depict what I perceived to be a deep imbalance between the reporting on the deaths of hundreds of African patients and the personal tragedy of just two westerners.”

The result was a striking illustration: a sea of beds filled with black African patients writhing in agony, while the media notice only the single white patient.

“It’s natural that people care more about what’s happening closer to their lives and realities,” Carrilho said. “But I also think we all have a responsibility to not view what is not our immediate problem as a lesser problem. The fact that thousands of deaths in Africa are treated as a statistic, and that one or two patients inside our borders are reported in all their individual pain, should be cause for reflection.”

More:

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/oct/12/cuba-leads-fights-against-ebola-africa

Judi Lynn

(163,195 posts)AMA Journal of Ethics®

Illuminating the Art of Medicine

Policy Forum

Mar 2021

Peer-Reviewed

Health Equity, Cuban Style

C. William Keck, MD, MPH

Citation

PDF

Altmetric

Abstract

The United States has not yet decided to ensure that every citizen has access to health care services at reasonable cost. The United States spends more on health care than any other country by far. Yet the health status of the US population, when compared with that of like nations, remains poor. The US system does not operate efficiently, fares poorly in terms of health equity, and has an illness and injury care industry with many uncoordinated “systems” focused on treating individuals rather than on improving health status. There are lessons for us in Cuba’s health system.

We Don’t Get What We Pay For

The United States has not yet decided to ensure that every citizen has access to health care at a reasonable cost. As many readers know, the United States spends more on health care than any other country by far—$11 072 per capita in 2019.1 Yet the health status of the US population, when compared with that of like nations, remains at the bottom of the list.2 We also fare poorly in terms of health equity, with large disparities in health status between subpopulation groups.3 We are not getting what we pay for largely because the United States does not have a health care system that runs efficiently. Instead, we have an illness and injury care industry containing many different, uncoordinated “systems” focused on treating individuals rather than on improving health status.

There are many examples of countries that have found a way to provide universal access for their populations using variations of 3 models: socialized care, socialized payment, or highly regulated private insurance.4 Some of our national policymakers seem largely unwilling to learn from others if doing so would require change at home, but if we hope to do better, learn and change we must!

I suggest that, in addition to examining the approaches chosen in upper-income countries similar to our own, we also look at Cuba, a middle-income country. Since the 1959 overthrow of the Batista regime, Cuba has focused on developing a health system that would be accessible to all at no cost to the patient, with an emphasis on reducing health inequities. It has had remarkable success, changing its population health status (life expectancy, infant mortality, infectious disease mortality, older adult health) from that typical of a low- to middle-income country to a high-income country, all while suffering for 60 years under the impact of the strongest embargo enacted by the United States.5 In an early nod to an important social determinant of health, the Cuban government understood that health and economic development are closely linked to population education levels, so universal access to free education through professional training was instituted, with the result that Cuba is ranked 13th in the world in literacy—with an almost 100% literacy rate—while the United States is ranked 125th with a literacy rate of 86%.6 Cuba’s experience indicates that population health can be achieved in the absence of wealth if existing resources are well organized and applied effectively to accomplish measurable health, education, and social welfare goals.

Lessons From Cuba

So, how has Cuba managed to improve health status so dramatically? Space constraints preclude a detailed analysis here, but a brief discussion of how Cuba has improved its infant mortality rates can provide some insight into how Cuba has improved its population’s health status overall and diminished health inequities. Infant mortality is one of the measures generally accepted as reflective of a health system’s effectiveness.7 In the United States, the infant mortality rate in 2017 stood at 5.8 deaths per 1000 live births, but that average number hides the wide range of infant death rates across individual states—from 3.7 to 8.6 per 1000 live births in 2017—or between racial groups—from 11.4 per 1000 live births among non-Hispanic Black people to 3.6 per 1000 live births among Asians in 2016.8 In comparison, infant mortality in Cuba stood at 38.7 per 1000 live births in 1970, and fell to 4.0 per 1000 live births in 2018, with a range of 2.1 to 6.3 between Cuba’s 15 provinces.9 In 2019, mortality under 5 years of age was 7.0 per 1000 live births in the United States and 5.0 per 1000 live births in Cuba.10

More:

https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/home