Scrivener7

(53,800 posts)But buy today. There is still 23% to go on the S&P before we're back to the highs for the year.

You can never catch the low, but maybe you can catch it on the way back up.

(Unless it drops more tomorrow. Which is always possible.)

progree

(11,541 posts)all-time-high (4797 on Jan 3) on the S&P 500.

A peculiarity of how percentage changes are calculated: ( to - from ) / from * 100%. So for example a drop from 4 to 3 is a 25% drop, but a rise from 3 to 4 is a 33.3% rise.

Scrivener7

(53,800 posts)PoindexterOglethorpe

(27,076 posts)So you could still buy.

But trying to time the market is always a fool's game.

multigraincracker

(34,717 posts)I bought Ford at $1.89/share. At the time it seemed like a huge risk to buy 1,500 shares.

I’m just trilled it’s paying dividends again. All I need or want now is income. Old and winding down now.

progree

(11,541 posts)And then I returned to my original allocation when it had returned to its previous high. It's called buying stocks on sale (in my case broad-based equity funds). It is a form of market timing (buying stocks when the stock market is down). Can you tell me when that has not worked? Perhaps in the Great Depression one would have had to wait a long long time to get above water again. But other than that? Since WWII? Anyway its worked for me. Every time so far. So if "trying to time the market is always a fool's game", well, if making some extra money on cheap stocks is being a fool ![]() , then I'm glad I'm a fool.

, then I'm glad I'm a fool.

Also I note that rebalancing to get back to one's target allocation is a form of market timing. Rebalancing to maintain an asset allocation is pretty much a universally recommended strategy. I never heard it called foolish or a fool's errand before.

Ditto bucket strategies, where for those who need to withdraw from their investments/savings occasionally to meet living expenses or emergencies, they suggest withdrawing from cash or other non-equities when the market is down (so that one is not selling their equities cheap). And withdrawing from equities when the market is doing well (depending on the state of where one's asset allocation is to the target allocation). This too is a form of market timing. I've never ever heard of bucket strategies like this called foolish.

PoindexterOglethorpe

(27,076 posts)I have a financial advisor who has done very well for me over the 20 or so years I've been with him.

He got me into a couple of annuities about a decade ago. Annuities tend to be trashed here, and I don't fully understand why. He got me into mine, as I said, about a decade or so ago, and I started taking payouts perhaps five years ago. They give me a guaranteed income stream. I'm not likely to live long enough (age 74 at present) to outlive their value. Whatever is left over when I die, goes to my heir.

I know that there are many here reading this who are comfortable and happy to make their own decisions about what to buy and sell. Personally, I am not comfortable with that, and so I'm very happy to have my financial advisor. One thing I like about what he's done for me, is that he's minimized risk, so that I never lose as much in a downturn as the downturn itself. True, I don't do as well on the upside, but the minimizing of downside is well worth it.

Here's something he sent me recently, which is quite mind-boggling, I think.

How many years did the stock market have big loss, 12% or more? 7

How many years with a small loss, 0% to 12%? 18

How many with a small gain .1% to 11.9%? 20

How many with large gain, 12% or more? 50

So think about it. Nearly half the time the market has a large gain, and only a very small time does it have a big loss. And keep in mind that the past 95 years starts out before the crash of '29. Think about it.

Yes, in the decade of the 1930s, the stock market was relatively terrible, but if you'd started buying in 1930, and kept on buying, you'd have made incredible gains. Also, I recall reading (and it may well have been in the book about the crash by John Kenneth Galbraith) that during the Depression, stocks that paid dividends, were so undervalued, that they were selling at prices that made the dividend payments huge. I don't want to try to remember the percentages, but I recall they were vastly above what today would be considered and excellent dividend. But because people were terrified to buy, they went unsold.

Here's something to keep in mind: The Crash of 1929 and the subsequent Depression was a one-off. There were a lot of specific and unique things that built up to it, that really don't apply today. So every time you read something that says an equivalent crash is looming, know that's wrong. I am NOT saying a large drop in the market can't occur. Those large drops can and do happen. The downturns happen regularly. But the upturns vastly outweigh the downturns. So buying and holding for the long term is the best strategy.

progree

(11,541 posts)Last edited Tue Oct 4, 2022, 04:25 AM - Edit history (3)

You're just giving me a lecture on how great stocks are, and I agree (link).

(Late edit or perhaps you are agreeing with me and I'm entirely misreading your post, in which case, I apologize).

The substantial historic outperfomance on stocks is precisely exactly why I loaded up on some additional equities when the market had dropped by 20% (actually a broad-based equity mutual fund with a value tilt).

So please, when did buying say an S&P 500 index fund when the S&P 500 was down 20% or more *not* pay off? It's worked for me, and yet you claim "trying to time the market is always a fool's game."

ALWAYS? Not in my experience. Actually, never. Not in the market's historic experience either, though sometimes one may have to wait many years before the payoff.

And is that not an example of market timing? Yes it is. I'm making a conscious decision to increase my equity allocation based on the U.S. stock market being down 20% or more.

Rebalancing and bucket strategies are also examples of market timing. They tilt to increasing the equity allocation when equities are down.

What's foolish about those very widely recommended market timing strategies again?

I don't buy individual stocks either. I buy broad-based mutual funds and ETFs. I have only one individual stock that I inherited and kept. I sold the rest. I would never argue that buying one or a few stocks always pay off when the market is down. If I did, that would indeed accurately classify me a fool.

I don't recall reading anywhere that an equivalent crash (89% drop from peak to trough) is looming. And I certainly never said/wrote that I believe one is. And even if it is a slight possibility, I don't make financial decisions based on the worst possible outcome. But rather I make decisions based on probabilistic expected value with some hedging to protect against the worst possible outcomes (that's why I'm not 100% in stocks for example).

You seem to think I'm advocating sell sell sell because the end is coming. I am arguing precisely the exact opposite -- BUY WHEN THE MARKET IS DOWN. BECAUSE IT HAS WORKED EVERY TIME.

mahatmakanejeeves

(62,581 posts)At least for mutual funds. The price you pay is the closing price. If you buy on a disastrously down day, you buy the fund cheap. If you buy on an up day, you pay more.

BWdem4life

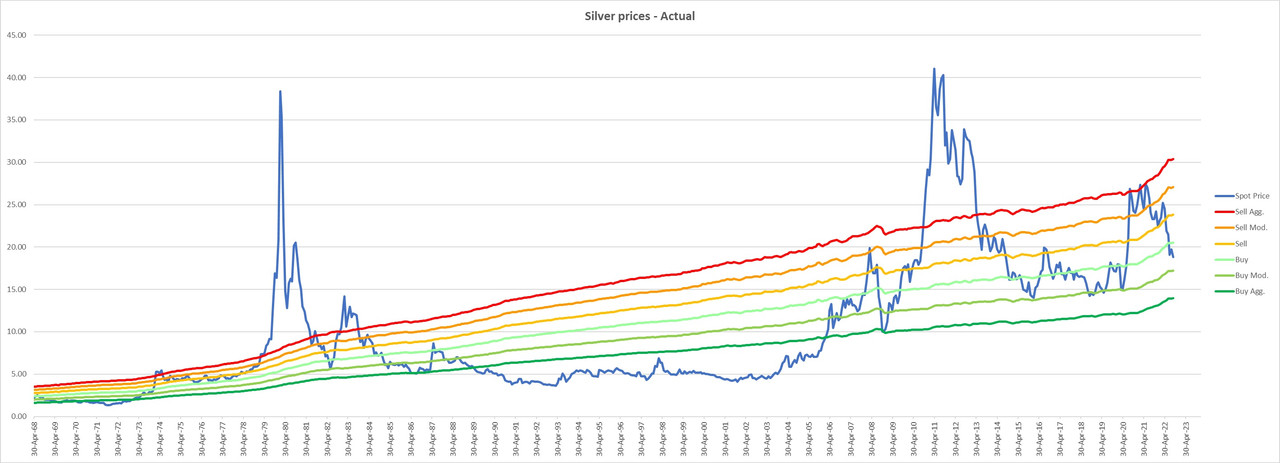

(2,504 posts)I'm sensing a possible crash by the end of the year. But who knows... Silver went up $1.51 overnight, a 7.8% increase. But I'm still bearish. Just a feeling.