Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

Editorials & Other Articles

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

American History

Related: About this forumOn this day, July 5, 1947, Larry Doby became the first black player in the American League.

Hat tip, the Richmond Times-Dispatch, in their "on this day" column

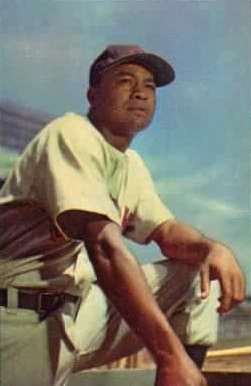

Larry Doby

Doby with the Indians in 1953

Lawrence Eugene Doby (December 13, 1923 – June 18, 2003) was an American professional baseball player in the Negro leagues and Major League Baseball (MLB) who was the second black player to break baseball's color barrier and the first black player in the American League.

{snip}

Major League Baseball career

Integration of American League (1947)

Cleveland Indians owner and team president Bill Veeck proposed integrating baseball in 1942, which had been informally segregated since the turn of the century, but this was rejected by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Veeck had begun the process of finding a young, talented player from the Negro leagues, and told a reporter in Cleveland that he would integrate the Indians' roster if he could find a black player with the necessary talent level who could withstand the taunts and pressure of being the first black athlete in the AL. The reporter suggested Doby, whom Veeck had seen at the Great Lakes Naval Training School. Doby's name was also mentioned when Veeck talked with reporters who covered the Negro leagues. Indians scout Bill Killefer rated Doby favorably and perhaps just as important for Veeck, reported Doby's off-field behavior was not a concern. The Dodgers rated Doby their top young Negro league prospect. But unlike the Brooklyn Dodgers' Branch Rickey, who signed Robinson one full season before bringing him to the National League, Veeck used a different strategy, letting Doby remain with the {Newark} Eagles instead of bringing him through the Indians' farm system. He told the Pittsburgh Courier, "One afternoon when the team trots out on the field, a Negro player will be out there with it."

While Rickey declined to pay for the purchasing rights of Robinson while he played for the Kansas City Monarchs, Veeck was "determined to buy Doby's contract from the Eagles" and had no problem paying purchasing rights. Effa Manley, business manager for the Eagles, believed her club's close relationship with the New York Yankees might put Doby in a Yankees uniform, but they did not take interest in him. Veeck finalized a contract deal for Doby with Manley on July 3. Veeck paid her a total of $15,000 for her second baseman—$10,000 for taking him from the Eagles and another $5,000 once it was determined he would stay with the Indians for at least 30 days. After Manley agreed to Veeck's offer, she stated to him, "If Larry Doby were white and a free agent, you'd give him $100,000 to sign as a bonus." The press were not told that Doby had been signed by the Indians as Veeck wanted to manage how fans in Cleveland would be introduced to Doby. "I moved slowly and carefully, perhaps even timidly", Veeck said. The Eagles had a doubleheader on July 4 but Doby, who had a .415 batting average and 14 home runs to that point in the season, only played in the first as Veeck sent his assistant and public relations personnel member, Louis Jones, for Doby. The two took a train from Newark to Chicago where the Indians were scheduled to play the Chicago White Sox the next day.

On July 5, with the Indians in Chicago in the midst of a road trip, Doby made his debut as the second black baseball player after Robinson to play in the majors after establishment of the baseball color line. Veeck hired two plainclothes police officers to accompany Doby as he went to Comiskey Park. Player-manager Lou Boudreau initially had a hard time finding a place in the lineup for Doby, who had played second base and shortstop for most of his career. Boudreau himself was the regular shortstop, while Joe Gordon was the second baseman. That day, Doby met his new teammates for the first time. "I walked down that line, stuck out my hand, and very few hands came back in return. Most of the ones that did were cold-fish handshakes, along with a look that said, 'You don't belong here", Doby reminisced years later. Four of Doby's teammates did not shake his hand, and of those, two turned their backs to Doby when he tried to introduce himself. During warm-ups, Doby languished for minutes while his teammates interacted with one another. Not until Joe Gordon asked Doby to play catch with him was Doby given the chance to engage. Gordon befriended Doby and became one of his closest friends on the team.

Doby entered the game in the seventh inning as a pinch-hitter for relief pitcher Bryan Stephens and recorded a strikeout. In the 1949 movie The Kid from Cleveland, Veeck tells the story that Gordon struck out on three swings in his immediate at-bat after Doby to save face for his new teammate. However, Doby's second strike was the result of a foul ball, both the Associated Press and Chicago Tribune stated Doby struck out on five pitches instead of three, and in addition, Gordon was standing on third base during Doby's at-bat. From Pride and Prejudice: The Biography of Larry Doby:

The Indians had a doubleheader against the White Sox on Sunday, July 6, for which 31,566 were in attendance; it was estimated that approximately 30 percent of the crowd were black. Some congregations of black churches let out early while others walked immediately from Sunday service to Comiskey Park. Boudreau had Doby pinch-hit in the first game but for the second, listed him a starter at first base, a position Doby was not expected to fill when the Indians brought him up to play at second base. Doby had played the position before with the Eagles but was without a proper mitt for first base and met much resistance when attempts were made to borrow one from teammates, including first baseman Eddie Robinson, whom Boudreau had asked Doby to replace that day. Doby said only because Gordon asked in the clubhouse to borrow one of the first baseman's mitts did he have one to use in the second game of the doubleheader as earlier direct requests from Doby were rejected. The mitt was loaned by a White Sox player. Boudreau recounts an incident where Robinson refused the mitt to Doby, but when asked by Indians traveling secretary Spud Goldstein, Robinson obliged. It was the only game Doby started for the remainder of the season. Doby recorded his first major league hit in four at-bats and had an RBI in a 5–1 Indians win.

A columnist wrote in the Plain Dealer on July 8: "Cleveland's man in the street is the right sort of American, as was evidenced right solidly once more by the response to the question: 'How does the signing of Larry Doby by the Indians strike you? Said the man in the street: Can he hit? ... That's all that counts." Conversely, Doby was criticized from players both active and retired. Noted former player Rogers Hornsby said, after watching Doby play one time in 1947:

In his rookie year, Doby hit .156 (5-for-32) in 29 games. He played four games at second base and one each at first base and shortstop. Throughout the season, he talked with Jackie Robinson via telephone, the two encouraging each other. "And Jackie and I agreed we shouldn't challenge anybody or cause trouble—or we'd both be out of the big leagues, just like that. We figured that if we spoke out, we would ruin things for other black players." After his rookie season, Doby again pursued time on the basketball court and appeared with the Paterson Crescents of the American Basketball League after signing a contract in January 1948. He was the first black player to join the league.

{snip}

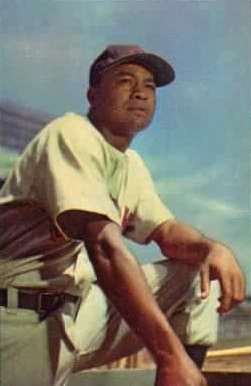

Doby with the Indians in 1953

Lawrence Eugene Doby (December 13, 1923 – June 18, 2003) was an American professional baseball player in the Negro leagues and Major League Baseball (MLB) who was the second black player to break baseball's color barrier and the first black player in the American League.

{snip}

Major League Baseball career

Integration of American League (1947)

Cleveland Indians owner and team president Bill Veeck proposed integrating baseball in 1942, which had been informally segregated since the turn of the century, but this was rejected by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Veeck had begun the process of finding a young, talented player from the Negro leagues, and told a reporter in Cleveland that he would integrate the Indians' roster if he could find a black player with the necessary talent level who could withstand the taunts and pressure of being the first black athlete in the AL. The reporter suggested Doby, whom Veeck had seen at the Great Lakes Naval Training School. Doby's name was also mentioned when Veeck talked with reporters who covered the Negro leagues. Indians scout Bill Killefer rated Doby favorably and perhaps just as important for Veeck, reported Doby's off-field behavior was not a concern. The Dodgers rated Doby their top young Negro league prospect. But unlike the Brooklyn Dodgers' Branch Rickey, who signed Robinson one full season before bringing him to the National League, Veeck used a different strategy, letting Doby remain with the {Newark} Eagles instead of bringing him through the Indians' farm system. He told the Pittsburgh Courier, "One afternoon when the team trots out on the field, a Negro player will be out there with it."

While Rickey declined to pay for the purchasing rights of Robinson while he played for the Kansas City Monarchs, Veeck was "determined to buy Doby's contract from the Eagles" and had no problem paying purchasing rights. Effa Manley, business manager for the Eagles, believed her club's close relationship with the New York Yankees might put Doby in a Yankees uniform, but they did not take interest in him. Veeck finalized a contract deal for Doby with Manley on July 3. Veeck paid her a total of $15,000 for her second baseman—$10,000 for taking him from the Eagles and another $5,000 once it was determined he would stay with the Indians for at least 30 days. After Manley agreed to Veeck's offer, she stated to him, "If Larry Doby were white and a free agent, you'd give him $100,000 to sign as a bonus." The press were not told that Doby had been signed by the Indians as Veeck wanted to manage how fans in Cleveland would be introduced to Doby. "I moved slowly and carefully, perhaps even timidly", Veeck said. The Eagles had a doubleheader on July 4 but Doby, who had a .415 batting average and 14 home runs to that point in the season, only played in the first as Veeck sent his assistant and public relations personnel member, Louis Jones, for Doby. The two took a train from Newark to Chicago where the Indians were scheduled to play the Chicago White Sox the next day.

On July 5, with the Indians in Chicago in the midst of a road trip, Doby made his debut as the second black baseball player after Robinson to play in the majors after establishment of the baseball color line. Veeck hired two plainclothes police officers to accompany Doby as he went to Comiskey Park. Player-manager Lou Boudreau initially had a hard time finding a place in the lineup for Doby, who had played second base and shortstop for most of his career. Boudreau himself was the regular shortstop, while Joe Gordon was the second baseman. That day, Doby met his new teammates for the first time. "I walked down that line, stuck out my hand, and very few hands came back in return. Most of the ones that did were cold-fish handshakes, along with a look that said, 'You don't belong here", Doby reminisced years later. Four of Doby's teammates did not shake his hand, and of those, two turned their backs to Doby when he tried to introduce himself. During warm-ups, Doby languished for minutes while his teammates interacted with one another. Not until Joe Gordon asked Doby to play catch with him was Doby given the chance to engage. Gordon befriended Doby and became one of his closest friends on the team.

Doby entered the game in the seventh inning as a pinch-hitter for relief pitcher Bryan Stephens and recorded a strikeout. In the 1949 movie The Kid from Cleveland, Veeck tells the story that Gordon struck out on three swings in his immediate at-bat after Doby to save face for his new teammate. However, Doby's second strike was the result of a foul ball, both the Associated Press and Chicago Tribune stated Doby struck out on five pitches instead of three, and in addition, Gordon was standing on third base during Doby's at-bat. From Pride and Prejudice: The Biography of Larry Doby:

After the game, Doby quickly showered and dressed without incident in the Cleveland clubhouse. His escort, Louis Jones, then took him not to the Del Prado Hotel downtown, where the Indians players stayed, but to the black DuSable Hotel in Chicago's predominantly black South Side, near Comiskey Park. The segregated arrangement established a pattern, on Doby's first day, that he would be compelled to follow, in spring training and during the regular season, in many cities, throughout his playing career.

The Indians had a doubleheader against the White Sox on Sunday, July 6, for which 31,566 were in attendance; it was estimated that approximately 30 percent of the crowd were black. Some congregations of black churches let out early while others walked immediately from Sunday service to Comiskey Park. Boudreau had Doby pinch-hit in the first game but for the second, listed him a starter at first base, a position Doby was not expected to fill when the Indians brought him up to play at second base. Doby had played the position before with the Eagles but was without a proper mitt for first base and met much resistance when attempts were made to borrow one from teammates, including first baseman Eddie Robinson, whom Boudreau had asked Doby to replace that day. Doby said only because Gordon asked in the clubhouse to borrow one of the first baseman's mitts did he have one to use in the second game of the doubleheader as earlier direct requests from Doby were rejected. The mitt was loaned by a White Sox player. Boudreau recounts an incident where Robinson refused the mitt to Doby, but when asked by Indians traveling secretary Spud Goldstein, Robinson obliged. It was the only game Doby started for the remainder of the season. Doby recorded his first major league hit in four at-bats and had an RBI in a 5–1 Indians win.

A columnist wrote in the Plain Dealer on July 8: "Cleveland's man in the street is the right sort of American, as was evidenced right solidly once more by the response to the question: 'How does the signing of Larry Doby by the Indians strike you? Said the man in the street: Can he hit? ... That's all that counts." Conversely, Doby was criticized from players both active and retired. Noted former player Rogers Hornsby said, after watching Doby play one time in 1947:

Bill Veeck did the Negro race no favor when he signed Larry Doby to a Cleveland contract. If Veeck wanted to demonstrate that the Negro has no place in major league baseball, he could have used no subtler means to establish the point. If he were white he wouldn't be considered good enough to play with a semi-pro club. He is fast on his feet but that lets him out. He hasn't any other quality that could possibly recommend him.

In his rookie year, Doby hit .156 (5-for-32) in 29 games. He played four games at second base and one each at first base and shortstop. Throughout the season, he talked with Jackie Robinson via telephone, the two encouraging each other. "And Jackie and I agreed we shouldn't challenge anybody or cause trouble—or we'd both be out of the big leagues, just like that. We figured that if we spoke out, we would ruin things for other black players." After his rookie season, Doby again pursued time on the basketball court and appeared with the Paterson Crescents of the American Basketball League after signing a contract in January 1948. He was the first black player to join the league.

{snip}

InfoView thread info, including edit history

TrashPut this thread in your Trash Can (My DU » Trash Can)

BookmarkAdd this thread to your Bookmarks (My DU » Bookmarks)

1 replies, 323 views

ShareGet links to this post and/or share on social media

AlertAlert this post for a rule violation

PowersThere are no powers you can use on this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

ReplyReply to this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

Rec (1)

ReplyReply to this post

1 replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

On this day, July 5, 1947, Larry Doby became the first black player in the American League. (Original Post)

mahatmakanejeeves

Jul 2024

OP

underpants

(186,611 posts)1. Thanks. That was a troubling but good read.