MARCH 30, 2017

During Argentina’s military dictatorship, some 500 babies were born in secret torture centers or kidnapped. A group of grandmothers spent the next four decades searching for them, becoming activists, then icons. But hundreds remained missing. One of them was named Martín.

By Bridget Huber

Photographs by Sarah Pabst

When Stella Montesano went into labor in December 1976, the other detainees on her cellblock pounded on the walls and doors to alert the guards. About six weeks earlier, a squad of masked men with guns had come to the apartment where Stella lived with her husband, Jorge Ogando, in La Plata, Argentina. The men threw hoods over Stella’s and Jorge’s heads, handcuffed them, and dragged them out the door just after dawn. They left the couple’s 3-year-old daughter, Virginia, behind in her bed.

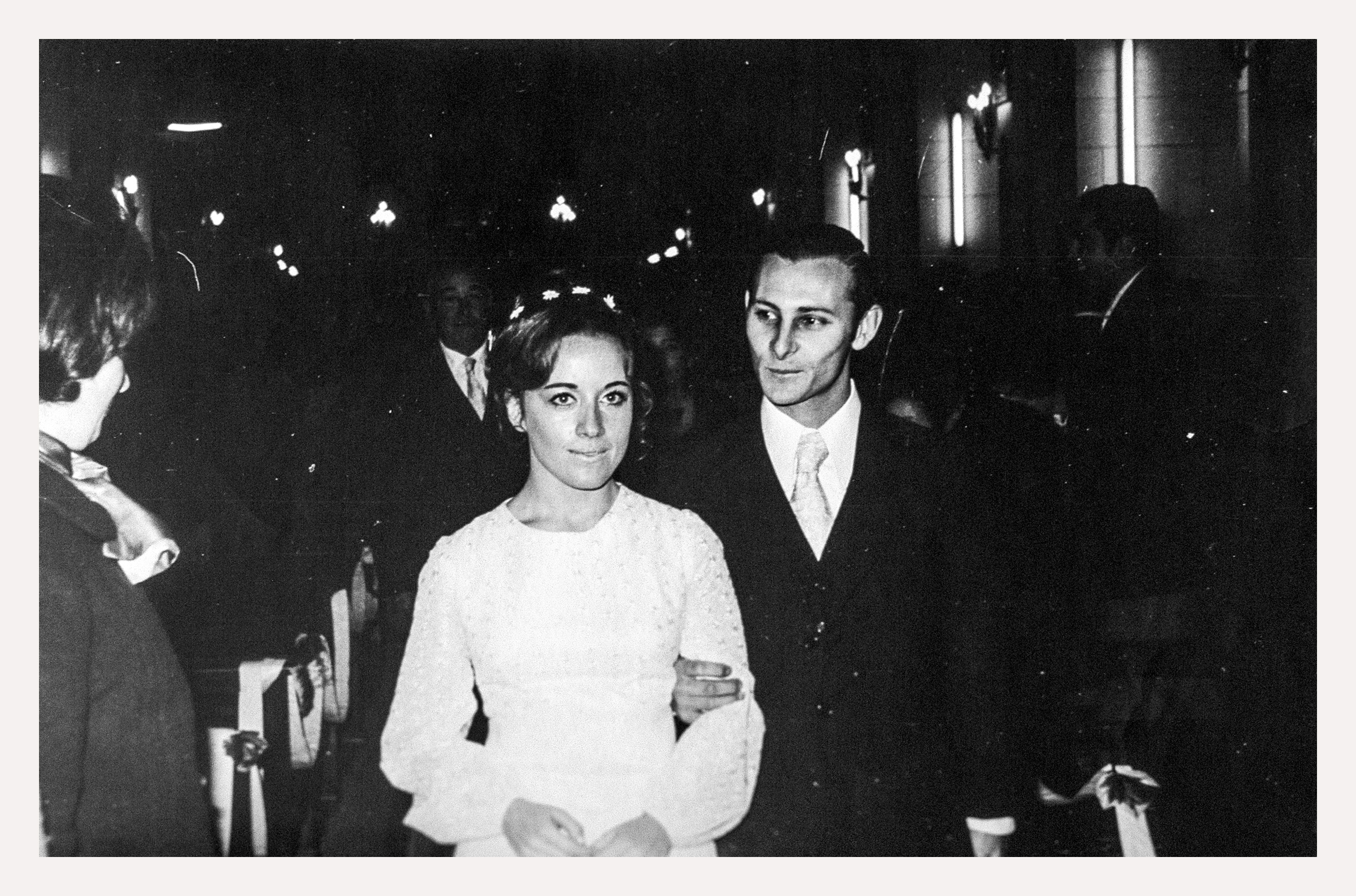

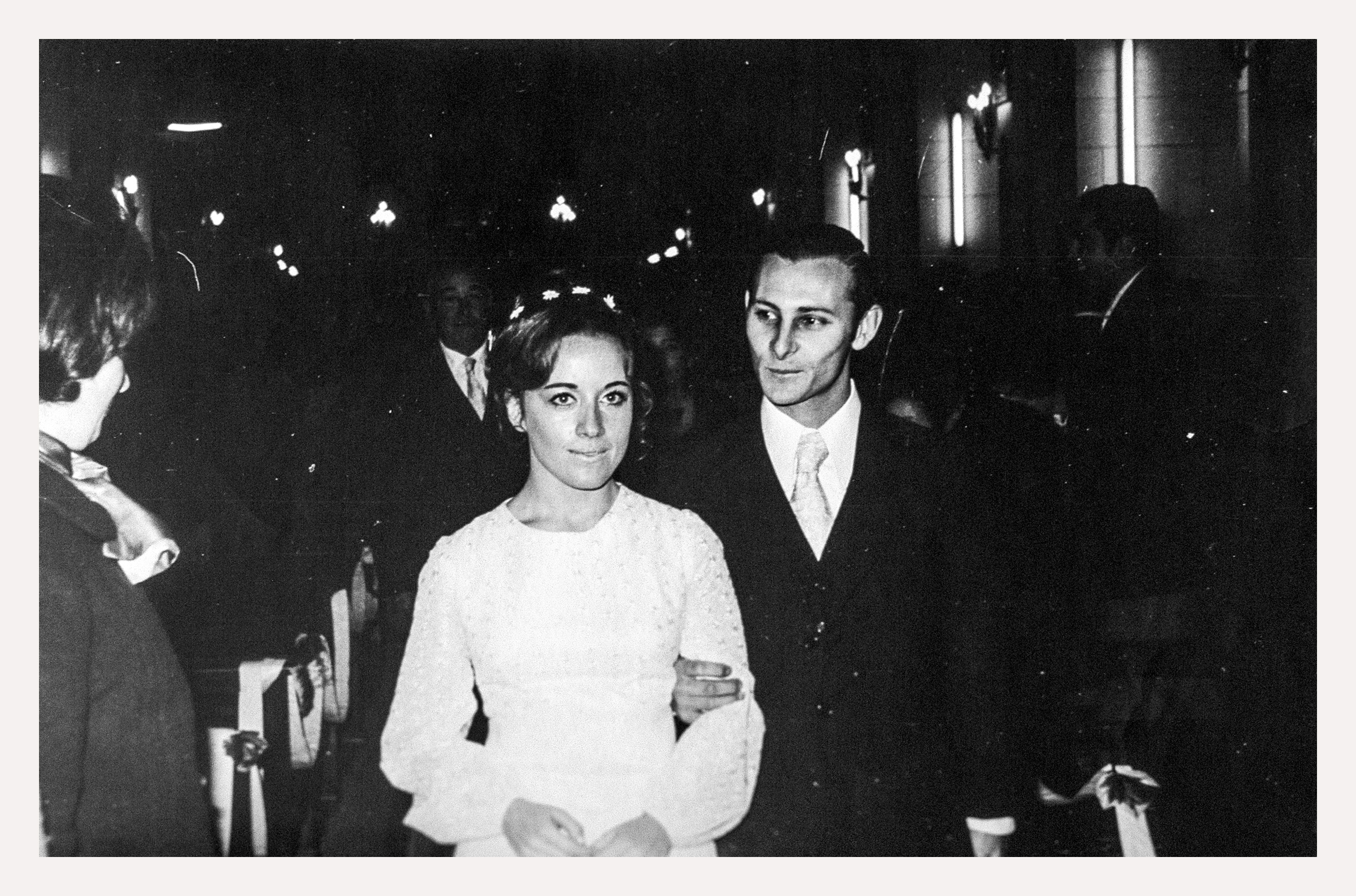

Stella and Jorge's wedding, 1972

Stella and Jorge were taken to a secret prison about 30 miles away. The detention center, known as the Pozo de Banfield, or the Banfield Pit, was one of a circuit of torture centers operated by the army and police. Jorge and Stella — a bank employee and a lawyer, respectively — were both in their late 20s. The other detainees included a group of teenagers who’d been campaigning for a student discount on bus fare, a journalist, a transgender woman, and a member of an armed leftist group. The prisoners were kept tightly bound, blindfolded, and half-naked on the floor. Many had been badly beaten or had burns in their mouths and on their genitals from being shocked with electricity during interrogations. Rape and mock executions were routine. The prisoners would go days without eating, forced to piss and defecate on the floor.

Those who survived would later recall mostly sounds and sensations — a blasting radio that didn’t quite conceal the screams of people being tortured, a thirst so overwhelming it drove one woman to drink urine, the ominous boot steps of guards on the stairs. Some would recall another sound, too — the cries of newborn babies.

Stella gave birth in the prison’s kitchen, attended by a doctor, Jorge Antonio Bergés. Bergés presided over torture sessions in several secret prisons, survivors would later testify — he’d revive people so they could be tortured again — but he took particular interest in the pregnant detainees. He called them “jewels” and assigned other prisoners to watch over them. He’d tell the guards not to rape them, to rape other women instead.

Stella was handcuffed and blindfolded for much of her labor. But the baby was born healthy; a boy with light hair and blue eyes, who looked just like Virginia had when she was born. When asked what she wanted to call him, Stella said Martín — the name she and Jorge had picked weeks earlier. Several days later, Stella returned to the cellblock, despondent and sick with an infection. The guards had taken the baby, saying they’d bring him to her family. But Stella had managed to keep a piece of Martín’s umbilical cord. The prisoners passed it from hand to hand, cell to cell, until it reached her husband, Jorge. It was all he would ever know of his son.

Pozo de Banfield, the detention center where Stella and Jorge were detained and Martín was born. It has been dedicated a memorial.

. . .

Some 500 children are thought to have disappeared during the dictatorship. Some were stolen when their parents were abducted, but most were born in Argentina’s torture centers. After women gave birth, they were considered as worthless as any other prisoner. In the Pozo de Banfield, the guards often made new mothers clean the makeshift maternity room right after delivery. Some postpartum women were dropped from planes into the Río de la Plata’s turbid waters; others were executed and dumped into mass graves or burned in the crematoriums that operated day and night. In a final erasure, the dictatorship’s operatives stripped the women’s babies of their identities — many were kept as spoils of war by people close to the regime. Others were abandoned at orphanages or sold on the black market.

More:

https://story.californiasunday.com/the-living-disappeared/

= new reply since forum marked as read

= new reply since forum marked as read