Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

Editorials & Other Articles

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

African American

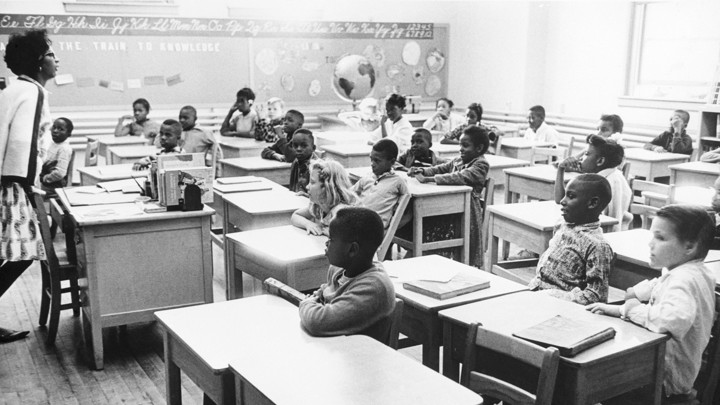

Showing Original Post only (View all)The Secret Network of Black Teachers Behind the Fight for Desegregation [View all]

Missed this a few months ago.For 25 years, the Emory University professor Vanessa Siddle Walker has studied and written about the segregated schooling of black children. In her latest book, The Lost Education of Horace Tate: Uncovering the Hidden Heroes Who Fought for Justice in Schools, Walker tells the little-known story of how black educators in the South—courageously and covertly—laid the groundwork for 1954’s Brown v. Board of Education and weathered its aftermath.

The tale is told primarily through the life of Horace Tate, an acclaimed Georgia classroom teacher, principal, and one-time executive director of the Georgia Teachers and Education Association (GTEA), an organization for black educators founded in 1878. Later in his career, he became the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from the University of Kentucky; at the time, Georgia still banned black students from state doctoral programs. Walker first met Tate in 2000. Over the course of the next two years, he told her about clandestine meetings among and outreach to influential black educators, lawyers, and community members tracing back to the 1940s. He also revealed black teachers’ secret and skillful organizing to demand equality and justice for African American children in Southern schools. After Tate’s death in 2002 at the age of 80, Walker continued a 15-year exploration, relying on Tate’s extensive archives to expose the full picture of how black educators mounted civil rights battles—in the years preceding and immediately following the Brown decision—to protect the interests of black children.

Walker: To overturn Plessy v. Ferguson—the 1896 Supreme Court case upholding the separate-but-equal doctrine—you have to have access to the people in the South. But if you’re in the NAACP’s national office in New York, how do you know who in the South will be a plaintiff? How do you launch a movement when you can’t really work well in the South because of the hostile climate? At the same time, black teachers in the South have data on school conditions and teaching resources and they know the plaintiffs, but they can’t let it be known that they’re part of the movement or they’ll lose their jobs. So it’s a perfect partnership. Black educators called themselves hidden provocateurs—these are the people figuring out, on a local level, how to provoke change and maneuver to get better facilities and more funding. To have it publicly known would undermine what they were trying to do. The generations of black people who followed learned the script that they wanted us to know.

Anderson: Black citizens who challenged Jim Crow segregation by rejecting racial subordination faced violence, intimidation, and economic ruin. Talk about the personal and emotional costs borne by black educators who were fighting for black children during the civil-rights era.

Walker: There are obvious losses—black teachers were fired and demoted. Wonderful black principals were put in charge of running school buses. They were humiliated because they had once been leaders in their communities. Some of them had to relocate and move north. But there are costs that we forget—like losing control over what black children learned.

The black educators taught math and science and everything else as best as they could with the limited resources that they had. You also saw the infusion of blackness in their classrooms. They were teaching black children how to be resilient in a segregated society. They seeded the civil-rights movement with this curriculum.

Those of us who reflect on the civil-rights era naturally think about people losing jobs and status. But to me just as important is understanding that they lost the chance to instill in another generation the ability to think about racial progress. We lost things that were foundational. We have to know the breadth of the costs, to understand both how we got to present-day conditions and how to think about moving forward.

6 replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies