White holes: What we know about black holes' neglected twins [View all]

By Charlie Wood Contributions from Daisy Dobrijevic published February 24, 2022

White holes are returning to the experimental spotlight

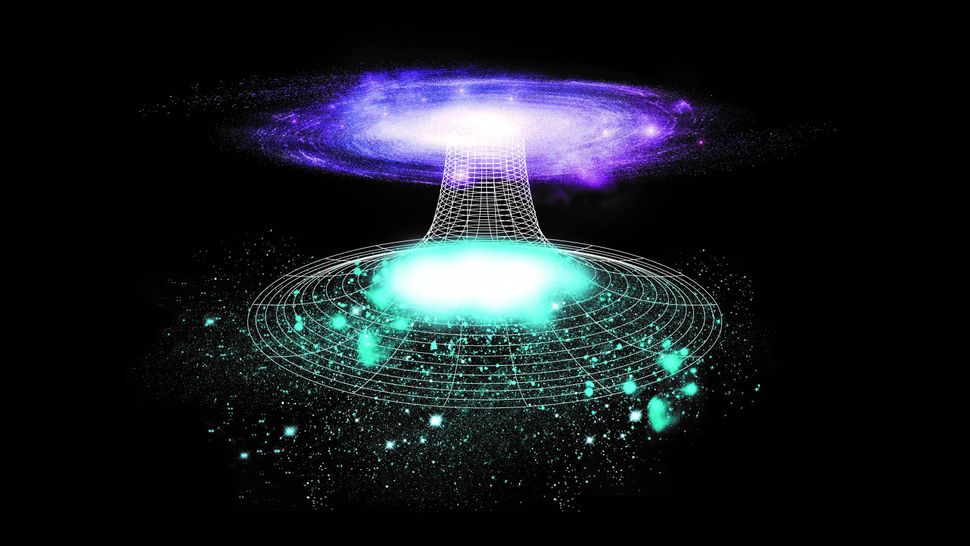

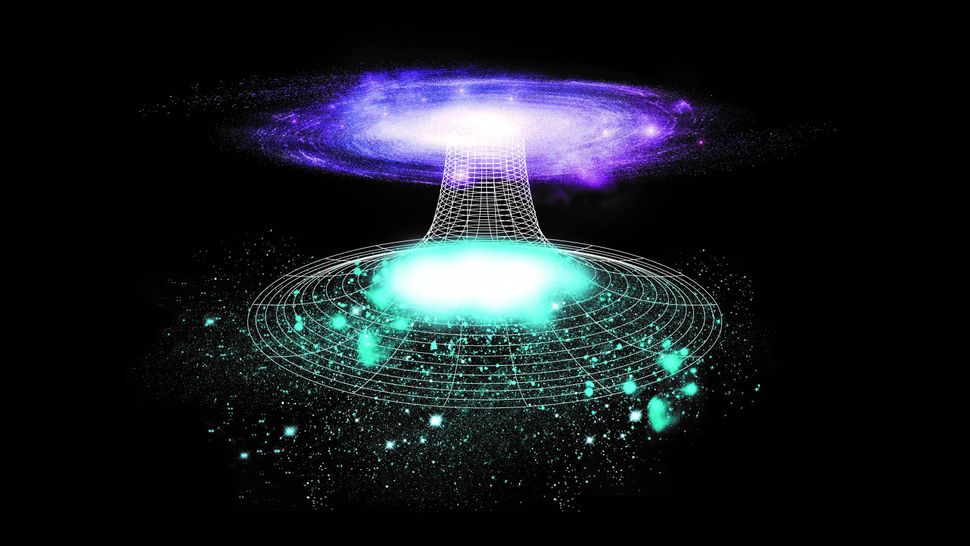

White holes are theoretical cosmic regions that function in an opposite way to black holes. (Image credit: Future/Adam Smith)

White holes are theoretical cosmic regions that function in the opposite way to black holes. Just as nothing can escape a black hole, nothing can enter a white hole.

White holes were long thought to be a figment of general relativity born from the same equations as their collapsed star brethren, black holes. More recently, however, some theorists have been asking whether these twin vortices of spacetime may be two sides of the same coin.

Physicists describe a white hole as a black hole's "time reversal," a video of a black hole played backwards, much as a bouncing ball is the time-reversal of a falling ball. While a black hole's event horizon is a sphere of no return, a white hole's event horizon is a boundary of no admission — space-time's most exclusive club. No spacecraft will ever reach the region's edge.

To a spaceship crew watching from afar, a white hole looks exactly like a black hole. It has mass. It might spin. A ring of dust and gas could gather around the event horizon — the bubble boundary separating the object from the rest of the universe. But if they kept watching, the crew might witness an event impossible for a black hole — a belch. "It's only in the moment when things come out that you can say, 'ah, this is a white hole,'" said Carlo Rovelli, a theoretical physicist at the Centre de Physique Théorique in France.

More:

https://www.space.com/white-holes.html